Alfred Hitchcock

- psufootball07

- Joined: Wed Apr 02, 2008 2:52 pm

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Hmmm, yeah I guess I will give The Paradine Case and Under Capricorn a shot, as well as possibly Torn Curtain and Family Plot. However having just seen it, I Confess is just one of the Hitchcock films that doesnt nearly get the recognition it deserves.

- domino harvey

- Dot Com Dom

- Joined: Wed Jan 11, 2006 2:42 pm

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Reverse that, Torn Curtain and Family Plot are both far superior to the Paradine Case and Under Capricorn

-

karmajuice

- Joined: Tue Jun 10, 2008 10:02 am

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

There is one scene in Torn Curtain that outweighs all of the merits of the other three combined. Definitely watch Torn Curtain for that -- even if the rest is mostly forgettable.

- thirtyframesasecond

- Joined: Mon Apr 02, 2007 1:48 pm

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Nice work. What made me chuckle was the automatically generated ads.

Hitchcock’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith – Why It’s Awesome by Katie Richardson

The Dramatic Carole Lombard

R KELLY ISSUES STATEMENT REGARDING FORMER PUBLICIST’S ALLEGATIONS….

Hitchcock’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith – Why It’s Awesome by Katie Richardson

The Dramatic Carole Lombard

R KELLY ISSUES STATEMENT REGARDING FORMER PUBLICIST’S ALLEGATIONS….

-

Vic Pardo

- Joined: Fri May 01, 2009 6:24 am

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

TOPAZ has some great scenes in it and an interesting Euro-cast, but it's not a good movie. But it should be seen. Flawed Hitchcock is still better than most current fare. And TOPAZ's great scenes are esp. memorable, including the opening and the scene at Harlem's Theresa Hotel, where Castro stays.

- Antoine Doinel

- Joined: Sat Mar 04, 2006 1:22 pm

- Location: Montreal, Quebec

- Contact:

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

First it was Charlie Chaplin, now a new photoshoot has Jessica Alba in recreated stills from Hitchcock films.

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

I suppose that I should add in my favourite Hitchcock films but they'll really just be the obvious ones in the top tier: Rear Window, Psycho, Shadow Of A Doubt, The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes, The Lodger, Blackmail and so on (I'd also add Vertigo which I'm not particularly fond of but which on dispassionate calculation obviously belongs in the top tier too).

While the classics are endlessly fascinating films and as close to 'perfect' as they come, I find myself constantly being drawn to my list of 'second tier' Hitchcocks - the films with dated special effects; with slightly awkward, forced or over-emphatic moments; with 'difficult' performances, and so on. I find however that the flaws are part of what adds to the distinctive charm of the films and gives them a strange power, in addition to revealing by comparison the techniques in the 'perfect' films in rougher, or more difficult to handle forms. The films I'd place in this 'second tier' of flawed diamonds that either anticipate or spin off from a perfect core of an idea that is fully realised in the top tier would be Rebecca, The Birds, Frenzy, Marnie and the film I want to talk about more today, Rope.

Rope (1948)

Rope would have to place near the top of this second group for me. I find it endlessly rewatchable and entertaining. Rope has some obvious flaws: the performances can be too obvious in their foreshadowing and ironic implications and the long take concept can often distract attention from the story and uncharitably may be described as a gimmick used to jazz up an overly theatrical piece.

Incidentally, I don't really understand why such comments are often used in a negative manner - I love films that emphasise a claustrophobic, stagebound set and in the case of Rope the setting seems more than appropriate - a nightmarish pre-Exterminating Angel dinner party where the guests are trapped by niceties into unwittingly participating in a sick joke, but eventually in the inability to leave for their summer home to dump the body the single set shifts into becoming a prison for the two murderous boys instead.

Rope, with its deep focus photography, frames within frames and overlapping soundtracks of conversations that are faded in and out to provide emphasis (or an ironic, flippant or heartbreaking off-hand comment that counterpoints with the main conversation) is fascinating in itself, but also anticipates Rear Window's further developments of these ideas, in which both sounds and images compete for the main character's (and viewers!) attention.

I especially liked the way that important action and dialogue is staged. At certain times the camera swoops in to emphasise a detail that goes unseen at the time so that the audience notices it first (the snapped champagne glass; the rope hanging out of the chest; the hiding of the cigarette case) and then pulls back into the main action until the characters themselves bring this element fully into the flow of the story by noticing such things themselves or making a comment on it. It makes the audience omniscient and also belies the stage origins in an interesting way by introducing extreme close ups into a stagey piece.

It mixes the best elements of film (the chance to see a characters reactions, or significant objects in close up) with the best elements of theatre (the idea that you can pick out elements of the action that you want to focus on while the 'main' emphasis is elsewhere, should you wish to. Probably best shown in the way that the camera pans away from the circuitous interrogation of Brandon and Phillip about where David could be to the chest being cleared away by the maid, making several trips back and forth until the secret is almost revealed to the assembled company.) Of course there are some detrimental aspects of both included too! (the performances are a little too broad at times which would play great to the stalls but are a little too 'in your face' here; and the work is constantly in danger of being overwhelmed by the technique and all the little touches that over emphasise most points, as if afraid that the audience will not catch them unless explicitly pointed out).

I also liked the way that more and more of the action involves off screen space as the film goes on (culminating in that fantastically chilling and almost ghostly sequence of Rupert's voiceover describing how he thinks the murder happened over pans over the empty room), and that the camera often pulls away from the characters either in shame at watching touchingly naive and ignorant characters being manipulated or in disgust at Brandon and Phillip's actions.

It is interesting that after the main titles the film begins with the close up of the strangling, entering to discover the cause of the commotion just at the moment that a character makes their exit (contrasting with the 'no escape' strangling in Frenzy, which is a similar scene played from bantering beginning until brutal aftermath). Even though we miss most of the 'best part' just catching the end of that act makes the whole deed that much more shocking and would seem to be the action that paralyses the camera into its long take pattern - as if it, as well as the viewer, cannot look away due to their disbelief at the initial action and the unity of time constantly reminds us throughout of the presence of the murder just minutes earlier. There is no jump to later on to safely isolate the innocent characters from the killers in their own scene of the story (perhaps making this even more radical than Rear Window, where all the characters are discreetly housed in their different apartments, at least until everything collapses together at the end and people become aware of their neighbours, and their neighbours aware of them, for the first time), and this just emphasises the guests having a party at a crime scene - it doesn't look like a crime scene, everything is neat and tidy, even if traces may remain but the murder opening the film focuses the audiences attention almost entirely onto the hidden body, as much as it keeps hold of Phillip's attention, wishing that opening moment was just a trick of imagination but knowing that it really did occur. The camera, like Phillip's gaze, continually returns to the chest as if to confirm the presence or absence of the body, but apart from the tell-tale rope at the beginning, there are no clues left until it is opened and reveals David (or not as the case may be - I often wonder what would have happened if in that short time between the maid leaving and Rupert coming back Brandon and Phillip had actually moved the body somewhere else in the apartment. With the chest then being revealed to be empty, would Rupert still have continued with his suspicions. It is unlucky for our duo that they do not think to do this in time, just to be safe in the short term. However seeing them move the body later on in the film would have violated that unstated principle I speak of above, where once David goes into the chest, we never see any trace of him again and he remains in a limbo state until the final confrontation, and even then the audience does not see the body, only Rupert's reaction to it).

I feel that the common reaction to the long takes of the film as just a gimmick being played around with is slightly misguided. Sure it is a novelty as much as Lady In The Lake ran with its first-person conceit to the bitter end, but I feel Hitchcock shows just how important editing is in this film by the way he moves the camera in for close ups or different set ups and we get shown the transition moments rather than having them edited out. Hitch also shows that he is not so wedded to the long take idea that he will not use editing at particularly significant moments. In fact he shows that when an edit does come after a long sustained shot, it adds an extra power and momentum to the new shot in the sequence.

As well as Rear Window, I found myself wondering whether the film also anticipates The Birds in the relationship between Kenneth and Janet. The way that all the partygoers leave in a bunch, nervous and fearful (though for someone else rather than their own safety), and especially in that tentative reconnection between Janet and Kenneth leaving together to offer each other comfort, I couldn't help but think of the final scene with Melanie and the Brenners coming together in the face of a traumatic event.

I also see Rupert's final speech as a kind of precursor to Psycho's psychiatrist. His comments about bringing Brandon and Phillip (but in particular Brandon) to justice play as someone righteously angry. Yet Rupert is flawed in having espoused views on murder earlier on that could have been seen as having an influence on their actions. In that sense there is an undercurrent of backpeddaling from his charges, suggesting that his comments were more intellectual and humourous posturing to see what kind of reaction he can elicit from people (i.e. Rupert is the pre-Internet version of a troll?)

It stuck me as a similar kind of plotting to The Most Dangerous Game's big game hunter hero eventually becoming the prey. And similarly neither 'hero' really recognises the implications for their own stance in others heinous acts - they are allowed to place blame squarely onto crazed evil doers.

The almost gleeful way that Rupert shouts that society is going to kill them to punish them for their own killing seems to neatly sidestep that society is in a constantly negotiated set of values. As Nazi Germany showed, is something being condoned by a society really the true marker of whether an action is a correct, or 'moral' one?

So in the end Rupert gets his ideas explored to their fullest extent, and gets to retain the moral high ground and societal status. Much as an audience can take pleasure in a murder mystery without actually having to kill someone themselves to do so!

While the classics are endlessly fascinating films and as close to 'perfect' as they come, I find myself constantly being drawn to my list of 'second tier' Hitchcocks - the films with dated special effects; with slightly awkward, forced or over-emphatic moments; with 'difficult' performances, and so on. I find however that the flaws are part of what adds to the distinctive charm of the films and gives them a strange power, in addition to revealing by comparison the techniques in the 'perfect' films in rougher, or more difficult to handle forms. The films I'd place in this 'second tier' of flawed diamonds that either anticipate or spin off from a perfect core of an idea that is fully realised in the top tier would be Rebecca, The Birds, Frenzy, Marnie and the film I want to talk about more today, Rope.

Rope (1948)

Rope would have to place near the top of this second group for me. I find it endlessly rewatchable and entertaining. Rope has some obvious flaws: the performances can be too obvious in their foreshadowing and ironic implications and the long take concept can often distract attention from the story and uncharitably may be described as a gimmick used to jazz up an overly theatrical piece.

Incidentally, I don't really understand why such comments are often used in a negative manner - I love films that emphasise a claustrophobic, stagebound set and in the case of Rope the setting seems more than appropriate - a nightmarish pre-Exterminating Angel dinner party where the guests are trapped by niceties into unwittingly participating in a sick joke, but eventually in the inability to leave for their summer home to dump the body the single set shifts into becoming a prison for the two murderous boys instead.

Rope, with its deep focus photography, frames within frames and overlapping soundtracks of conversations that are faded in and out to provide emphasis (or an ironic, flippant or heartbreaking off-hand comment that counterpoints with the main conversation) is fascinating in itself, but also anticipates Rear Window's further developments of these ideas, in which both sounds and images compete for the main character's (and viewers!) attention.

I especially liked the way that important action and dialogue is staged. At certain times the camera swoops in to emphasise a detail that goes unseen at the time so that the audience notices it first (the snapped champagne glass; the rope hanging out of the chest; the hiding of the cigarette case) and then pulls back into the main action until the characters themselves bring this element fully into the flow of the story by noticing such things themselves or making a comment on it. It makes the audience omniscient and also belies the stage origins in an interesting way by introducing extreme close ups into a stagey piece.

It mixes the best elements of film (the chance to see a characters reactions, or significant objects in close up) with the best elements of theatre (the idea that you can pick out elements of the action that you want to focus on while the 'main' emphasis is elsewhere, should you wish to. Probably best shown in the way that the camera pans away from the circuitous interrogation of Brandon and Phillip about where David could be to the chest being cleared away by the maid, making several trips back and forth until the secret is almost revealed to the assembled company.) Of course there are some detrimental aspects of both included too! (the performances are a little too broad at times which would play great to the stalls but are a little too 'in your face' here; and the work is constantly in danger of being overwhelmed by the technique and all the little touches that over emphasise most points, as if afraid that the audience will not catch them unless explicitly pointed out).

I also liked the way that more and more of the action involves off screen space as the film goes on (culminating in that fantastically chilling and almost ghostly sequence of Rupert's voiceover describing how he thinks the murder happened over pans over the empty room), and that the camera often pulls away from the characters either in shame at watching touchingly naive and ignorant characters being manipulated or in disgust at Brandon and Phillip's actions.

It is interesting that after the main titles the film begins with the close up of the strangling, entering to discover the cause of the commotion just at the moment that a character makes their exit (contrasting with the 'no escape' strangling in Frenzy, which is a similar scene played from bantering beginning until brutal aftermath). Even though we miss most of the 'best part' just catching the end of that act makes the whole deed that much more shocking and would seem to be the action that paralyses the camera into its long take pattern - as if it, as well as the viewer, cannot look away due to their disbelief at the initial action and the unity of time constantly reminds us throughout of the presence of the murder just minutes earlier. There is no jump to later on to safely isolate the innocent characters from the killers in their own scene of the story (perhaps making this even more radical than Rear Window, where all the characters are discreetly housed in their different apartments, at least until everything collapses together at the end and people become aware of their neighbours, and their neighbours aware of them, for the first time), and this just emphasises the guests having a party at a crime scene - it doesn't look like a crime scene, everything is neat and tidy, even if traces may remain but the murder opening the film focuses the audiences attention almost entirely onto the hidden body, as much as it keeps hold of Phillip's attention, wishing that opening moment was just a trick of imagination but knowing that it really did occur. The camera, like Phillip's gaze, continually returns to the chest as if to confirm the presence or absence of the body, but apart from the tell-tale rope at the beginning, there are no clues left until it is opened and reveals David (or not as the case may be - I often wonder what would have happened if in that short time between the maid leaving and Rupert coming back Brandon and Phillip had actually moved the body somewhere else in the apartment. With the chest then being revealed to be empty, would Rupert still have continued with his suspicions. It is unlucky for our duo that they do not think to do this in time, just to be safe in the short term. However seeing them move the body later on in the film would have violated that unstated principle I speak of above, where once David goes into the chest, we never see any trace of him again and he remains in a limbo state until the final confrontation, and even then the audience does not see the body, only Rupert's reaction to it).

I feel that the common reaction to the long takes of the film as just a gimmick being played around with is slightly misguided. Sure it is a novelty as much as Lady In The Lake ran with its first-person conceit to the bitter end, but I feel Hitchcock shows just how important editing is in this film by the way he moves the camera in for close ups or different set ups and we get shown the transition moments rather than having them edited out. Hitch also shows that he is not so wedded to the long take idea that he will not use editing at particularly significant moments. In fact he shows that when an edit does come after a long sustained shot, it adds an extra power and momentum to the new shot in the sequence.

As well as Rear Window, I found myself wondering whether the film also anticipates The Birds in the relationship between Kenneth and Janet. The way that all the partygoers leave in a bunch, nervous and fearful (though for someone else rather than their own safety), and especially in that tentative reconnection between Janet and Kenneth leaving together to offer each other comfort, I couldn't help but think of the final scene with Melanie and the Brenners coming together in the face of a traumatic event.

I also see Rupert's final speech as a kind of precursor to Psycho's psychiatrist. His comments about bringing Brandon and Phillip (but in particular Brandon) to justice play as someone righteously angry. Yet Rupert is flawed in having espoused views on murder earlier on that could have been seen as having an influence on their actions. In that sense there is an undercurrent of backpeddaling from his charges, suggesting that his comments were more intellectual and humourous posturing to see what kind of reaction he can elicit from people (i.e. Rupert is the pre-Internet version of a troll?)

It stuck me as a similar kind of plotting to The Most Dangerous Game's big game hunter hero eventually becoming the prey. And similarly neither 'hero' really recognises the implications for their own stance in others heinous acts - they are allowed to place blame squarely onto crazed evil doers.

The almost gleeful way that Rupert shouts that society is going to kill them to punish them for their own killing seems to neatly sidestep that society is in a constantly negotiated set of values. As Nazi Germany showed, is something being condoned by a society really the true marker of whether an action is a correct, or 'moral' one?

So in the end Rupert gets his ideas explored to their fullest extent, and gets to retain the moral high ground and societal status. Much as an audience can take pleasure in a murder mystery without actually having to kill someone themselves to do so!

- Tom Amolad

- Joined: Sun Jan 13, 2008 4:30 pm

- Location: New York

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Link's dead, but it can't be hotter than Slavoj, can it?Antoine Doinel wrote:First it was Charlie Chaplin, now a new photoshoot has Jessica Alba in recreated stills from Hitchcock films.

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Saboteur (1942)

"One ultimately turns into the thing one despises most"

I’m not certain that I would agree with the view that I have occasionally heard made about this film that by not explicitly mentioning Nazism as the terrorist group’s reasons for carrying out their acts of sabotage that it weakens the film. It might mean that the film does not work as effectively as short term propaganda, but I wonder if Nazism was downplayed to reach for a kind of universality. After all that was just the reasoning for those particular times but the nefarious organisation with powerful and respected backers behind the scenes manipulating events for their own gain could be applied to anything from other political regimes to organised crime (plus Nazism would likely have been at the forefront of contemporary audience's minds anyway and would not need to have been made explicit in order to have had that connection made).

Leaving the concept more universally applicable than ideologically specific also lets the theme become more about the fundamental decency and trust of the ‘common man’ set against the upper and middle classes. Either they are active plotters and schemers in the direction that their country takes or they are aspiring to reach that position themselves by allying themselves with the powerful. The idea of a façade of respectability concealing much darker activities could be applied to any period (and the charity fundraiser adds a particularly ironic touch – helping people in public while hurting their interests in private, or even thinking that you are doing the right things in both spheres. I was left thinking of American fundraising for the IRA with that sequence).

It also gets into the idea of things that should be working in our favour turning against us, perhaps most obviously shown in the opening sequence of the fire extinguisher being full instead of flammable fuel and only adding to the disaster. Here there is a sense that kindness of the public as individual is being manipulated and twisted as a whole on the subject of Barry Kane’s guilt. So to make a film that was intended with an overt propagandistic purpose either to work as a piece of isolationism or alternately as an entreaty to go to war would have undermined the theme of the film.

However the ‘fundamental decency of the ordinary person’ is often shown to be rather hotheaded and subject to personal infighting (i.e. the Siamese Twins taking polarised opinions on Barry’s guilt, seemingly just because the other feels differently), or interests (the truck driver’s wish to see some fun and excitement leading him to side with the criminal on the run), naïvety (the blind uncle so saintly certain that Barry is an innocent man) or fairly easy to manipulate through the mass media (Pat herself, taking news reports on the Barry’s guilt at face value and with a patriotism that means that if someone in authority says that turning Barry in is the right thing to do for her country, that means it truly must be the correct action. In a fun moment she only truly allies herself with Barry when the powerful and respected Tobin reveals his fundamental decency and innocence! So the bad guy, purely due to his powerful position, gives her the blessing to run to the innocent hero knowing that what he says about Barry must be true!)

The film seems in the same vein as the previous ‘man and woman go on the run together and try to solve a mystery’ film The 39 Steps, though Saboteur is far more overtly comic that the earlier film. However, as in the reasons behind Pat’s final alliance with Barry, it is an extremely ironic comedy. Some of the moments are laugh out loud funny, such as the maid bringing out a gun in alliance with Tobin her employer, or in a later sequence the unruffled manservant coshing our hero into unconsciousness and then getting back to more butler-ish duties without losing any of his cool! Or the moments where Mrs Sutton is told about the decent policeman unwilling to be paid off by Tobin being killed and instead being more concerned for the loss of Tobin’s “charming houseâ€! Or the "too bad we'll have to lose a good camera" line!

And the wonderful dance sequence where our couple affirm their love for each other has its sickly sweet nature undercut by occurring as the couple desperately try to find a way out of the ballroom, ending with Barry’s “This moment belongs to me. No matter what happens, they’ll never take it away from us†speech to Pat being immediately undercut by being whisked away by another dancer who cuts in on them! (With this dancer being suggested, in Barry’s relatively justified paranoid state, to be working for Tobin and having kidnapped Pat, but eventually it seems he was just an opportunistic lothario without any more complex agenda than that!)

There is also the sequence in the Radio City Music Hall where the real shootout mingles with the over-the-top amount of gunshots and squealing of the girl in the film itself, but this is also given a dark edge with the death of an innocent man in the crossfire.

And the irony that the real criminals are cultured and urbane all with children while our decent but desperate hero (whose decency in returning a $100 bill and revealing that he noticed Fry’s name from the envelope is what kickstarted the whole chain of events and caused the death of his friend) is forced into pretending he is a part of the evil organisation at one point, or has to gag his unwilling girlfriend to prevent her from calling the police. He even has to use a young child as a human shield at one point!

So he’s driven to dark surface acts to keep the inner decency alive, while the outer respectability of Tobin and Mrs Sutton etc conceals an inner corruption. Only the blind man in his cottage sanctuary is able to see through all the obfuscations and know him for an innocent man (a homage to Frankenstein?)

I feel that the ‘on the run’ sequences are the more clunky ones in the film, as our characters are given overly didactic moral lessons by the characters they meet. However they are also mostly saved by the ironic black humour that runs through them, such as the discussion of the life-saving properties of fire extinguishers by the truck driver; the syrupy speechifying of the blind uncle to Barry and Pat (and Barry’s far too smug reactions to being described as innocent as Pat looks on aghast!) being undercut by Pat proving to have not been taken in by this talk at all! Pat’s reactions seem to suggest that the younger generation are more cynical to over charitable views of people but at the same time are more prone to being taken in by simplistic propaganda statements and surface displays of civility and posturing as being ‘real’ ones, as perhaps best shown by her various ironically displayed billboards commenting on the action and shilling products at the same time!

The travelling carnival for me is perhaps a scene too far, partly due to it being the third consecutive ‘moral lesson in the common man’ for our characters as the characters hold an impromptu vote to show real democracy in action.

The aspect I like most about these ‘odd couple on the run’ films is that the hero and heroine, after some bickering, become a true couple in the sense that they work both independently and as a pair towards a common goal. Neither is extraneous to the action – one or the other of the pair may be waylaid at various points and in need of the help of the other, rather than just one of the pair becoming the damsel in distress.

I also like that Saboteur is a film full of failed escape attempts by our heroes, and that ‘luck’ (though bringing with it the associated guilt) is the reason for Barry not being killed in the opening fire rather than his friend. However circumstance and fate then twist in their favour and they have a few lucky breaks that help them to foil the plotter’s short term plans (and to come back into contact with Frank Fry after a long absence). In the end it is fate as much as planning that buffets all the characters, good or bad (I also like the way that the bomb exploding at the wrong time in the ship yard may reference Sabotage, although in this case the mistimed explosion becomes a lucky escape compared to what could have happened rather than a terrible tragedy that fulfils no ones goals.)

Another fun moment comes near the end where Pat tails Fry to the Statue of Liberty (with the breezed over and slightly unbelieveable comment from the cops about how it is a brilliant idea to isolate yourself on an island after carrying out a terrorist attack! However in a sense the cop is right and it is brilliant – for the structure and themes of the film however, more than for verisimilitude) and he shows that he is regaining some confidence and cockiness by coming on to her, with her reciprocating in order to buy time. Marian Keane would have a field day with the phallic way Pat toys with the rolled up tour guide! Though it does also turn her into a kind of living representation of the Statue of Liberty, so after many of the symbols of power being out of the ‘common man’s’ hands for most of the film by the cynical portrait of America’s ruling classes, finally it returns to the Statue as a true everyman symbol and helps to affirm the American ideal of everyone being deserving of a fair chance, unless they try to take such fair chances from others.

It is especially interesting that although the whole middle section details the activities of a wider organisation, the film kicks off and boils down to a face to face fight between wronged man and single ‘saboteur’. It adds a great personal significance to the final fight between Barry and Frank Fry (especially as the film bookends, or rather circles back, to Barry reliving the horror of watching someone die in front of his eyes while he is unable to save them, even if Fry is the bad guy who might deserve his fate). I love the absolute silence punctuated by terse commands by the characters as they hang from the torch, all being quiet until the final screaming plunge to death. While very inspirational of Vertigo there also seems to be a wonderful parallel here with the end of North By Northwest, as Barry is pulled up from perilously hanging from a national monument into the arms of his girl, while of course in the later film Grant pulls Eva Marie Saint into his arms, and his bed!

However ending with this cathartic moment for our heroes slighty obscures the way that the greater criminal masterminds are able to escape without punishment or even loss of status. The small time members of the organisation are the ones who pay the greatest price while those who are respectable and important enough continue on. It is a fascinating twofold end which completely fulfils the expectations of narrative entertainment but leaves the greater threat to liberty as an ongoing battle.

"One ultimately turns into the thing one despises most"

I’m not certain that I would agree with the view that I have occasionally heard made about this film that by not explicitly mentioning Nazism as the terrorist group’s reasons for carrying out their acts of sabotage that it weakens the film. It might mean that the film does not work as effectively as short term propaganda, but I wonder if Nazism was downplayed to reach for a kind of universality. After all that was just the reasoning for those particular times but the nefarious organisation with powerful and respected backers behind the scenes manipulating events for their own gain could be applied to anything from other political regimes to organised crime (plus Nazism would likely have been at the forefront of contemporary audience's minds anyway and would not need to have been made explicit in order to have had that connection made).

Leaving the concept more universally applicable than ideologically specific also lets the theme become more about the fundamental decency and trust of the ‘common man’ set against the upper and middle classes. Either they are active plotters and schemers in the direction that their country takes or they are aspiring to reach that position themselves by allying themselves with the powerful. The idea of a façade of respectability concealing much darker activities could be applied to any period (and the charity fundraiser adds a particularly ironic touch – helping people in public while hurting their interests in private, or even thinking that you are doing the right things in both spheres. I was left thinking of American fundraising for the IRA with that sequence).

It also gets into the idea of things that should be working in our favour turning against us, perhaps most obviously shown in the opening sequence of the fire extinguisher being full instead of flammable fuel and only adding to the disaster. Here there is a sense that kindness of the public as individual is being manipulated and twisted as a whole on the subject of Barry Kane’s guilt. So to make a film that was intended with an overt propagandistic purpose either to work as a piece of isolationism or alternately as an entreaty to go to war would have undermined the theme of the film.

However the ‘fundamental decency of the ordinary person’ is often shown to be rather hotheaded and subject to personal infighting (i.e. the Siamese Twins taking polarised opinions on Barry’s guilt, seemingly just because the other feels differently), or interests (the truck driver’s wish to see some fun and excitement leading him to side with the criminal on the run), naïvety (the blind uncle so saintly certain that Barry is an innocent man) or fairly easy to manipulate through the mass media (Pat herself, taking news reports on the Barry’s guilt at face value and with a patriotism that means that if someone in authority says that turning Barry in is the right thing to do for her country, that means it truly must be the correct action. In a fun moment she only truly allies herself with Barry when the powerful and respected Tobin reveals his fundamental decency and innocence! So the bad guy, purely due to his powerful position, gives her the blessing to run to the innocent hero knowing that what he says about Barry must be true!)

The film seems in the same vein as the previous ‘man and woman go on the run together and try to solve a mystery’ film The 39 Steps, though Saboteur is far more overtly comic that the earlier film. However, as in the reasons behind Pat’s final alliance with Barry, it is an extremely ironic comedy. Some of the moments are laugh out loud funny, such as the maid bringing out a gun in alliance with Tobin her employer, or in a later sequence the unruffled manservant coshing our hero into unconsciousness and then getting back to more butler-ish duties without losing any of his cool! Or the moments where Mrs Sutton is told about the decent policeman unwilling to be paid off by Tobin being killed and instead being more concerned for the loss of Tobin’s “charming houseâ€! Or the "too bad we'll have to lose a good camera" line!

And the wonderful dance sequence where our couple affirm their love for each other has its sickly sweet nature undercut by occurring as the couple desperately try to find a way out of the ballroom, ending with Barry’s “This moment belongs to me. No matter what happens, they’ll never take it away from us†speech to Pat being immediately undercut by being whisked away by another dancer who cuts in on them! (With this dancer being suggested, in Barry’s relatively justified paranoid state, to be working for Tobin and having kidnapped Pat, but eventually it seems he was just an opportunistic lothario without any more complex agenda than that!)

There is also the sequence in the Radio City Music Hall where the real shootout mingles with the over-the-top amount of gunshots and squealing of the girl in the film itself, but this is also given a dark edge with the death of an innocent man in the crossfire.

And the irony that the real criminals are cultured and urbane all with children while our decent but desperate hero (whose decency in returning a $100 bill and revealing that he noticed Fry’s name from the envelope is what kickstarted the whole chain of events and caused the death of his friend) is forced into pretending he is a part of the evil organisation at one point, or has to gag his unwilling girlfriend to prevent her from calling the police. He even has to use a young child as a human shield at one point!

So he’s driven to dark surface acts to keep the inner decency alive, while the outer respectability of Tobin and Mrs Sutton etc conceals an inner corruption. Only the blind man in his cottage sanctuary is able to see through all the obfuscations and know him for an innocent man (a homage to Frankenstein?)

I feel that the ‘on the run’ sequences are the more clunky ones in the film, as our characters are given overly didactic moral lessons by the characters they meet. However they are also mostly saved by the ironic black humour that runs through them, such as the discussion of the life-saving properties of fire extinguishers by the truck driver; the syrupy speechifying of the blind uncle to Barry and Pat (and Barry’s far too smug reactions to being described as innocent as Pat looks on aghast!) being undercut by Pat proving to have not been taken in by this talk at all! Pat’s reactions seem to suggest that the younger generation are more cynical to over charitable views of people but at the same time are more prone to being taken in by simplistic propaganda statements and surface displays of civility and posturing as being ‘real’ ones, as perhaps best shown by her various ironically displayed billboards commenting on the action and shilling products at the same time!

The travelling carnival for me is perhaps a scene too far, partly due to it being the third consecutive ‘moral lesson in the common man’ for our characters as the characters hold an impromptu vote to show real democracy in action.

The aspect I like most about these ‘odd couple on the run’ films is that the hero and heroine, after some bickering, become a true couple in the sense that they work both independently and as a pair towards a common goal. Neither is extraneous to the action – one or the other of the pair may be waylaid at various points and in need of the help of the other, rather than just one of the pair becoming the damsel in distress.

I also like that Saboteur is a film full of failed escape attempts by our heroes, and that ‘luck’ (though bringing with it the associated guilt) is the reason for Barry not being killed in the opening fire rather than his friend. However circumstance and fate then twist in their favour and they have a few lucky breaks that help them to foil the plotter’s short term plans (and to come back into contact with Frank Fry after a long absence). In the end it is fate as much as planning that buffets all the characters, good or bad (I also like the way that the bomb exploding at the wrong time in the ship yard may reference Sabotage, although in this case the mistimed explosion becomes a lucky escape compared to what could have happened rather than a terrible tragedy that fulfils no ones goals.)

Another fun moment comes near the end where Pat tails Fry to the Statue of Liberty (with the breezed over and slightly unbelieveable comment from the cops about how it is a brilliant idea to isolate yourself on an island after carrying out a terrorist attack! However in a sense the cop is right and it is brilliant – for the structure and themes of the film however, more than for verisimilitude) and he shows that he is regaining some confidence and cockiness by coming on to her, with her reciprocating in order to buy time. Marian Keane would have a field day with the phallic way Pat toys with the rolled up tour guide! Though it does also turn her into a kind of living representation of the Statue of Liberty, so after many of the symbols of power being out of the ‘common man’s’ hands for most of the film by the cynical portrait of America’s ruling classes, finally it returns to the Statue as a true everyman symbol and helps to affirm the American ideal of everyone being deserving of a fair chance, unless they try to take such fair chances from others.

It is especially interesting that although the whole middle section details the activities of a wider organisation, the film kicks off and boils down to a face to face fight between wronged man and single ‘saboteur’. It adds a great personal significance to the final fight between Barry and Frank Fry (especially as the film bookends, or rather circles back, to Barry reliving the horror of watching someone die in front of his eyes while he is unable to save them, even if Fry is the bad guy who might deserve his fate). I love the absolute silence punctuated by terse commands by the characters as they hang from the torch, all being quiet until the final screaming plunge to death. While very inspirational of Vertigo there also seems to be a wonderful parallel here with the end of North By Northwest, as Barry is pulled up from perilously hanging from a national monument into the arms of his girl, while of course in the later film Grant pulls Eva Marie Saint into his arms, and his bed!

However ending with this cathartic moment for our heroes slighty obscures the way that the greater criminal masterminds are able to escape without punishment or even loss of status. The small time members of the organisation are the ones who pay the greatest price while those who are respectable and important enough continue on. It is a fascinating twofold end which completely fulfils the expectations of narrative entertainment but leaves the greater threat to liberty as an ongoing battle.

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

"Everyone was sweet and pretty then, Charlie. The whole world. A wonderful world. Not like the world today. Not like the world now. It was great to be young then."

On watching this film again for the first time in years (yes, I have finally picked up that 14 disc Universal boxset to replace a good chunk of my videos! The menus are shockingly poor though with an awful version of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents tune over the top of them), I came up with a wacky theory that I'll throw onto the forum and see what people feel about it: that Shadow is a negative image version of Psycho.

Instead of the dark house and motel in Psycho being a festering site of murder and madness, in Shadow of a Doubt it is everything outside of the Newton's home that is falling into corruption and the family home is the last standout against the surrounding darkness. Both films also share the need for the delusion of 'normality' to keep everyday life going, when they are starting to lose touch with life as it is lived elsewhere in the country. This is probably best shown by the opening of the film where Uncle Charlie (in an amusing cowardly version of The Killers, though a few years before the Siodmak film, and sort of a precursor to Widmark's opening flight through the streets in Night and the City), gets chased through litter and rubble strewn streets of a city before running to the suburbs to hide out with his relatives. He's been corrupted by too much time in the city and knows it, which is probably why he finds such affinity with the younger Charlie, since they are alike in their wish to escape but she is still a wide-eyed innocent of the outside world. It therefore makes it ironic that it is Uncle Charlie who opens her eyes to the darker world beyond.

Uncle Charlie is presented as the primary infiltrator of corruption and dark ideas into the home but in a way, similarly to Psycho's dessicated mother, the rot is also taking place within the house itself - Charlie's wish for something to come along and shake the complacent family up at the beginning of the film; Ann's interest in knowledge and reading and comments on telephones suggesting that she is going to keep up with the times too; Joseph and Herbie's discussions of how to commit hypothetical murders act as the acceptable form of corruption, though jokey discussion about embezzlement is frowned upon while on duty at the bank by Joseph. Only Emmy, the mother, remains "pure" in her simple pleasures and she is the one who seems to become more insanely deluded as events progress, with the conflict between the two Charlies escalating while trying not to let her become aware of Uncle Charlie's corruption because, like an invalid, the shock could kill her by shattering her world.

But I do wonder about Emmy and whether she actually is aware of the goings on but because the whole weight of running the family home is dependent on her she cannot say anything herself, which leads to that incredible leaving party for Uncle Charlie where she seems to have a nervous breakdown while still keeping up appearances with a rictus grin of happiness on her face all the while. If she were to acknowledge the surrounding darkness then everything would collapse - the rest of the family are given the leeway to give in to their suspicions and casual murder discussions, she cannot. She seems aware at that point that this is a final parting from Uncle Charlie, the illusion will soon be shattered and this may be the last idyllic holiday together they will have. Luckily the best thing for her happens and with Uncle Charlie's 'accidental' death his good reputation is left secure. He can take his place as one of those people in the past who lived better, more moral lives than modern people do.

Similarly to Psycho the central house becomes isolated somewhat from the outside world, or stays still and is left behind while the world moves on without them and coarsens in attitudes at the same time as advancing. (At first the entire town looks like a bastion of perfect Americana, at least until the wonderful sequence of Uncle revealing to Niece the dark side she's never noticed before, including the heartbreakingly minor character of the schoolmate who has become a beaten down waitress at a seedy bar - an underlining of the family home and Charlie's coddled life being the greater delusion) The family then becomes a prime target for ego inflating surveys into 'representative American families' for their aggressive normality - the police know that this is a facade and play into it to gain access to the house while in a way Uncle Charlie is still in thrall to an imagined 'averageness' and wants to return to a time before corruption and this is the cause of his downfall.

There is the feeling from the film that childhood defines people's behaviour as adults. Uncle Charlie's accident when he fractured his skull (with the implication that this is the beginning of his wild and erratic behaviour) is the major example, but all through the film there is the feeling that the characters have already been set into roles that have been set into stone and that they cannot deviate from. Then this also leads into the theme of real and assumed roles - the pretence of being a particular, acceptable, person concealing another, true identity that others may find shocking. This is most obviously shown in the hero worship of the younger Charlie towards her Uncle (perhaps created only through her imagination - has she met her Uncle before then, or is it all created through her mother's stories of him?) turning into a fight to the death. And then this leads to a normal event taking on darker implications due to heightened sensitivity to casual talk of murder, for example, which prepares for a dark event of a death being given a whitewash of accidental respectability (both the train accident but also the plan to kill the younger Charlie and make it look like an accident).

I like the way that the welcoming front of the house becomes barred to young Charlie as her Uncle's superior status in the family and her own suspicions make it, and normality, out of bounds for her. She has to become furtive in her entrances and exits. It's another respectable facade that has been taken over by the bad guy, showing again just how delusional and manufactured any striving towards a completely perfect, or completely corrupt world is - it's all shades of grey. Even with Uncle Charlie gone the suburban facade has been thoroughly shattered for his namesake - just as her Uncle has been sacrificed to keep his name, and the name of his family intact (and brought the town together again), so Charlie has had a rite of passage and left her childhood behind, but has a new male figure in her life with the introduction of her cop boyfriend. She's moved beyond naivety and insularity of family life and into taking a part in society as a whole.

"Everyone was sweet and pretty then, Charlie. The whole world. A wonderful world. Not like the world today. Not like the world now. It was great to be young then."

On watching this film again for the first time in years (yes, I have finally picked up that 14 disc Universal boxset to replace a good chunk of my videos! The menus are shockingly poor though with an awful version of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents tune over the top of them), I came up with a wacky theory that I'll throw onto the forum and see what people feel about it: that Shadow is a negative image version of Psycho.

Instead of the dark house and motel in Psycho being a festering site of murder and madness, in Shadow of a Doubt it is everything outside of the Newton's home that is falling into corruption and the family home is the last standout against the surrounding darkness. Both films also share the need for the delusion of 'normality' to keep everyday life going, when they are starting to lose touch with life as it is lived elsewhere in the country. This is probably best shown by the opening of the film where Uncle Charlie (in an amusing cowardly version of The Killers, though a few years before the Siodmak film, and sort of a precursor to Widmark's opening flight through the streets in Night and the City), gets chased through litter and rubble strewn streets of a city before running to the suburbs to hide out with his relatives. He's been corrupted by too much time in the city and knows it, which is probably why he finds such affinity with the younger Charlie, since they are alike in their wish to escape but she is still a wide-eyed innocent of the outside world. It therefore makes it ironic that it is Uncle Charlie who opens her eyes to the darker world beyond.

Uncle Charlie is presented as the primary infiltrator of corruption and dark ideas into the home but in a way, similarly to Psycho's dessicated mother, the rot is also taking place within the house itself - Charlie's wish for something to come along and shake the complacent family up at the beginning of the film; Ann's interest in knowledge and reading and comments on telephones suggesting that she is going to keep up with the times too; Joseph and Herbie's discussions of how to commit hypothetical murders act as the acceptable form of corruption, though jokey discussion about embezzlement is frowned upon while on duty at the bank by Joseph. Only Emmy, the mother, remains "pure" in her simple pleasures and she is the one who seems to become more insanely deluded as events progress, with the conflict between the two Charlies escalating while trying not to let her become aware of Uncle Charlie's corruption because, like an invalid, the shock could kill her by shattering her world.

But I do wonder about Emmy and whether she actually is aware of the goings on but because the whole weight of running the family home is dependent on her she cannot say anything herself, which leads to that incredible leaving party for Uncle Charlie where she seems to have a nervous breakdown while still keeping up appearances with a rictus grin of happiness on her face all the while. If she were to acknowledge the surrounding darkness then everything would collapse - the rest of the family are given the leeway to give in to their suspicions and casual murder discussions, she cannot. She seems aware at that point that this is a final parting from Uncle Charlie, the illusion will soon be shattered and this may be the last idyllic holiday together they will have. Luckily the best thing for her happens and with Uncle Charlie's 'accidental' death his good reputation is left secure. He can take his place as one of those people in the past who lived better, more moral lives than modern people do.

Similarly to Psycho the central house becomes isolated somewhat from the outside world, or stays still and is left behind while the world moves on without them and coarsens in attitudes at the same time as advancing. (At first the entire town looks like a bastion of perfect Americana, at least until the wonderful sequence of Uncle revealing to Niece the dark side she's never noticed before, including the heartbreakingly minor character of the schoolmate who has become a beaten down waitress at a seedy bar - an underlining of the family home and Charlie's coddled life being the greater delusion) The family then becomes a prime target for ego inflating surveys into 'representative American families' for their aggressive normality - the police know that this is a facade and play into it to gain access to the house while in a way Uncle Charlie is still in thrall to an imagined 'averageness' and wants to return to a time before corruption and this is the cause of his downfall.

There is the feeling from the film that childhood defines people's behaviour as adults. Uncle Charlie's accident when he fractured his skull (with the implication that this is the beginning of his wild and erratic behaviour) is the major example, but all through the film there is the feeling that the characters have already been set into roles that have been set into stone and that they cannot deviate from. Then this also leads into the theme of real and assumed roles - the pretence of being a particular, acceptable, person concealing another, true identity that others may find shocking. This is most obviously shown in the hero worship of the younger Charlie towards her Uncle (perhaps created only through her imagination - has she met her Uncle before then, or is it all created through her mother's stories of him?) turning into a fight to the death. And then this leads to a normal event taking on darker implications due to heightened sensitivity to casual talk of murder, for example, which prepares for a dark event of a death being given a whitewash of accidental respectability (both the train accident but also the plan to kill the younger Charlie and make it look like an accident).

I like the way that the welcoming front of the house becomes barred to young Charlie as her Uncle's superior status in the family and her own suspicions make it, and normality, out of bounds for her. She has to become furtive in her entrances and exits. It's another respectable facade that has been taken over by the bad guy, showing again just how delusional and manufactured any striving towards a completely perfect, or completely corrupt world is - it's all shades of grey. Even with Uncle Charlie gone the suburban facade has been thoroughly shattered for his namesake - just as her Uncle has been sacrificed to keep his name, and the name of his family intact (and brought the town together again), so Charlie has had a rite of passage and left her childhood behind, but has a new male figure in her life with the introduction of her cop boyfriend. She's moved beyond naivety and insularity of family life and into taking a part in society as a whole.

-

broadwayrock

- Joined: Thu Jun 22, 2006 9:47 am

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

A rare 1973 Hour long interview with Alfred Hitchcock has recently been uploaded to youtube

- Murdoch

- Joined: Sun Apr 20, 2008 11:59 pm

- Location: Upstate NY

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

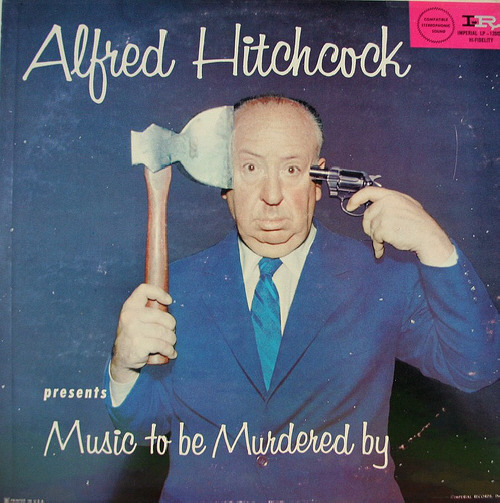

This may have been posted before, but I found this hilarious album cover and, since it's Halloween, had to share it:

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Following on from my comments on Rope earlier, especially my enthusiasm over the empty shot with camera movements as Rupert hypothesises on how the potential murder occured, I had not remembered until watching it again last night but the earlier Rebecca has a very similar sequence of Maxim and "I" in the beach house in which he confesses the events leading to Rebecca's death with pans across the empty space in which the fateful (and possibly inaccurate) event's occured.

Also after reading David Bordwell's recent blog post on the use of bedposts in film, there was a fun moment when Mrs Danvers is leading "I" on a tour of Rebecca's bedroom when just as she pulls out Rebecca's negligee and as the camera moves around the edge of the bed before she puts he hand inside the garment and utters the classic sexually charged line about how thin the material is and invites "I" to touch it, a wonderfully (and strangely given the non-male presence in the scene!) phallic bedpost comes between the pair. It sort of splits "I" off from Mrs Danvers (and the bed) and her recollections of Rebecca as well as arriving at the climax of this sequence of personifying/reanimating Rebecca through her possessions, so the bedpost in its drifting movement across the frame for a moment almost seems like is moving by itself after this invocation.

Also after reading David Bordwell's recent blog post on the use of bedposts in film, there was a fun moment when Mrs Danvers is leading "I" on a tour of Rebecca's bedroom when just as she pulls out Rebecca's negligee and as the camera moves around the edge of the bed before she puts he hand inside the garment and utters the classic sexually charged line about how thin the material is and invites "I" to touch it, a wonderfully (and strangely given the non-male presence in the scene!) phallic bedpost comes between the pair. It sort of splits "I" off from Mrs Danvers (and the bed) and her recollections of Rebecca as well as arriving at the climax of this sequence of personifying/reanimating Rebecca through her possessions, so the bedpost in its drifting movement across the frame for a moment almost seems like is moving by itself after this invocation.

- Cash Flagg

- Joined: Thu Jan 24, 2008 11:15 pm

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

So, who else wants this for Christmas?

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

"Hello! *waves* I'm modelling our range of life-sized bird fashion broches...the latest must have accessory for the busy gal about town! Comes with attachments to be worn on skirt, shoulder pad or for the truly daring, in the hair! For the 'well dressed but harrassed look' that tells everyone that I'm busy, I'm harried, but I still look good!"

-

zombeaner

- Joined: Sun Aug 27, 2006 2:24 pm

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

I got one for my birthday this year, it was my second best gift (after the new and first HDTV I've ever had)

-

Jonathan S

- Joined: Sat Jun 07, 2008 3:31 am

- Location: Somerset, England

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

No coffin accessory for the doll? (Hitch presented his Tippi doll that way to her daughter.)

-

HarryLong

- Joined: Tue Nov 25, 2008 12:39 pm

- Location: Lebanon, PA

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

I'm holding out for the Momma Bates doll ... with rocking chair & butcher knife.

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Marnie (1964)

"I'll advise Mr Rutland that you are available"

I grow to like Marnie more and more each time that I see it. I'm beginning to think of the film as a 'megamix' film, recasting a lot of tropes from Hitchcock's Hollywood period. For example the documentary on the DVD mentions links with To Catch A Thief - not just the original idea to cast Grace Kelly in the role, but also that Connery's character of Mark Rutland in Marnie has a sexual obsession with a thief similar to that which Kelly has for Cary Grant. I think there is an element of this but there are also huge influences from Vertigo (the literalised visions of neuroses; the remaking of a woman; the lustful but cold-shouldered female friend), The Birds (the relationship between Melanie Daniels and Annie Hayworth seems similar, though less overtly antagonistic as that between Marnie and Lil. The same with the relationship Melanie has with Cathy and that between Marnie and Jessie) and Rebecca (in the way that Marnie seems out of place in her new upper class milleu that she has married into. Also the cold and analytical relationship between her and Mark seems similar to that between Maxim and "I". Mark could also be seen to have killed off what he married Marnie for by the end of the film, only instead of "I"'s unsure girlish hesitancy replaced by the confident full partner in a relationship in Rebecca, Marnie's mysteriousness and wildness is fully explored and tamed by the end credits. Perhaps the most telling difference from Rebecca is that while Maxim keeps a house full of his first wife's memorabilia, the only evidence that Mark has of his first dead wife is a case of collectibles in his office, which are amusingly immediately destroyed by an 'act of Hitchcock' (or God, whichever you prefer) almost as soon as Marnie enters the office for the first time!)

Of course Psycho is another big element - such as in the mother's influence over the character's psychological state (Lil even ironically appropriates the "girl's best friend is her mother" line to comment on Marnie at one point!), or the petty thief being co-opted into another psychologically damaged person's world (though Mark in Marnie generally bears more of a relationship to the wealthy cowboy in Psycho than to Norman Bates!). But the big influence from Psycho would seem to be the psychiatrist's explanation of Norman at the end of the film - Marnie takes the vaguely unsatisfying ending, with all of its implied condescension and superiorities and makes an entire film about it.

The film is about the stripping out of Marnie's neuroses, apparently performed by Mark just for her benefit. But in no sense could this be considered an altruistic act - in fact this emphasis on Marnie's damaged psyche suggests an element of contempt for her by Mark, especially when his own actions go unchallenged by anyone else and the film as a whole.

It becomes about Mark 'breaking in' Marnie against her wishes, as one would break a wild animal (the persistent animal imagery is quite interesting, though at times a little too on the nose). There are again links back to The Birds here in the domestication of animals and of what could happen if they rebelled against human society, or if you let a domesticated animal run loose again after having taken moral responsibility for their actions (the "Back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels" line resonates in Marnie too, as Mark forces Marnie into a marriage pact to avoid jail, putting her into a privileged world but one which is just as much of a prison as if she had actually been arrested). In paying off the money that Marnie has stolen from Strutt (and then potentially paying the rest of the places where she has worked and then robbed from), along with the sense of the rich being able to buy themselves out of any sticky situation they get into, Mark introduces the idea of prostitution long before it gets raised in the final 'explanatory' flashback. Paying the money off in a way sullies Marnie still further as it illustrates the difference between an act performed for 'fun' or for compulsive reasons versus acts that may be morally wrong but which can be paid off, or which need to be performed in order to have enough money to live, for example Marnie's mother's prostitution. The scene following Marnie's robbery of Strutt shows her buying an ostentatious, and useless, fur scarf for her mother (a trophy from the hunt?) and paying for the upkeep of her favourite horse Faurio. So rather than needing the money because she is destitute, she is buying things in a childish manner, or to keep her inner child alive by maintaining her relationship with her mother and her 'toy' in her horse - expressions of a stunted childhood as illustrated by her (again, a little too on the nose) antagonistic relationship with the child her mother babysits, Jessie.

Mark either unknowingly (or knowingly but without a care for the cruel significance) morally dirties Marnie at the same time that he clears her name. He has a very cut off emotional side it seems, treating everything like a business transaction (again like Maxim de Winter). How much money will it cost to 'fix' things? He is driven, and has his authority to the viewer of the film undermined by, his own compulsions that he does not seem to want to acknowledge, if he is aware of them at all. Again this suggests his deep contempt for Marnie - that she needs to be solved and broken in a way that he himself does not.

And so to the honeymoon rape scene - and it is a rape, since Marnie is never a willing partner to it. Instead of being, say, 'raped into independence', it seems that this scene is about Mark raping Marnie into becoming a productive, and not destructive, member of society again, taking on the wifely duties of being available to her husband's needs whenever he wants them fulfilled. Even without the final explanation and 'mitigation' for the reason for Marnie's frigidity, and to give a horrible resonance to Mark's actions that it did not originally have, it is still an incredibly cruel and heartless way to make her face her demons. Again it raises ideas of prostitution - Mark has bought a wife, and she has to fulfil all of the obligations that come with that role.

In a way that brings me to why Mark would choose to become obessessed with Marnie, especially when it is such hard work to break her in and Lil is right there offering herself to Mark on a plate. It is about the hunt and capture, the thrill of the chase. Again there are links with The Birds here, and the available Annie Hayworth, while Melanie herself becomes the hunter and the rare bird at the same time - and then becomes perfect family material once she is passified at the end. The wild antics are just for show when what she really wants is stability - Marnie is the opposite in that Marnie herself wants the wildness, while Mark wants (or at least thinks he wants) her to become stabled. The superficially confident woman is broken down to be rebuilt in the way that her boyfriend wishes.

The hunt scene seems devastatingly pivotal in this transition, as Marnie first sees the things she previously enjoyed - the laws of the natural world and horse riding - become transfigured into a codified ritualistic, and highly mannered, act. The riders getting excited about the act of killing purely for pleasure prepare Marnie for bolting even before she becomes aware of the red of the rider's tunic. This drives her into spurring Faurio into a cross country gallop pursued by Lil (with Marnie symbolically becoming the prey now), until the accident when Faurio breaks his legs. I wonder if Marnie planned to cause the accident subconsciously so as to force her to destroy this significant element of her past life that she had placed such emotion onto? She pushes aside all requests for someone to shoot the animal for her (there never seems to be any shortage of volunteers!), needing to perform this action herself and kill off her past self.

Then the stage is set for the final confrontation, forced by Mark naturally, with her mother and explanation for her neuroses and sexual hang-ups. Once that is done, and mother abandoned, Mark has the perfect wife to mould to his wishes - or, after all her own attempts to escape earlier, will the tables now be turned and he will divorce her now that he has 'figured her out' and her mystery and interest for him have gone?

It is a really fascinating film, sometimes a little too obvious and mechanical in its allusions, but it definitely should be considered one of Hitchcock's major works.

"I'll advise Mr Rutland that you are available"

I grow to like Marnie more and more each time that I see it. I'm beginning to think of the film as a 'megamix' film, recasting a lot of tropes from Hitchcock's Hollywood period. For example the documentary on the DVD mentions links with To Catch A Thief - not just the original idea to cast Grace Kelly in the role, but also that Connery's character of Mark Rutland in Marnie has a sexual obsession with a thief similar to that which Kelly has for Cary Grant. I think there is an element of this but there are also huge influences from Vertigo (the literalised visions of neuroses; the remaking of a woman; the lustful but cold-shouldered female friend), The Birds (the relationship between Melanie Daniels and Annie Hayworth seems similar, though less overtly antagonistic as that between Marnie and Lil. The same with the relationship Melanie has with Cathy and that between Marnie and Jessie) and Rebecca (in the way that Marnie seems out of place in her new upper class milleu that she has married into. Also the cold and analytical relationship between her and Mark seems similar to that between Maxim and "I". Mark could also be seen to have killed off what he married Marnie for by the end of the film, only instead of "I"'s unsure girlish hesitancy replaced by the confident full partner in a relationship in Rebecca, Marnie's mysteriousness and wildness is fully explored and tamed by the end credits. Perhaps the most telling difference from Rebecca is that while Maxim keeps a house full of his first wife's memorabilia, the only evidence that Mark has of his first dead wife is a case of collectibles in his office, which are amusingly immediately destroyed by an 'act of Hitchcock' (or God, whichever you prefer) almost as soon as Marnie enters the office for the first time!)

Of course Psycho is another big element - such as in the mother's influence over the character's psychological state (Lil even ironically appropriates the "girl's best friend is her mother" line to comment on Marnie at one point!), or the petty thief being co-opted into another psychologically damaged person's world (though Mark in Marnie generally bears more of a relationship to the wealthy cowboy in Psycho than to Norman Bates!). But the big influence from Psycho would seem to be the psychiatrist's explanation of Norman at the end of the film - Marnie takes the vaguely unsatisfying ending, with all of its implied condescension and superiorities and makes an entire film about it.

The film is about the stripping out of Marnie's neuroses, apparently performed by Mark just for her benefit. But in no sense could this be considered an altruistic act - in fact this emphasis on Marnie's damaged psyche suggests an element of contempt for her by Mark, especially when his own actions go unchallenged by anyone else and the film as a whole.

It becomes about Mark 'breaking in' Marnie against her wishes, as one would break a wild animal (the persistent animal imagery is quite interesting, though at times a little too on the nose). There are again links back to The Birds here in the domestication of animals and of what could happen if they rebelled against human society, or if you let a domesticated animal run loose again after having taken moral responsibility for their actions (the "Back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels" line resonates in Marnie too, as Mark forces Marnie into a marriage pact to avoid jail, putting her into a privileged world but one which is just as much of a prison as if she had actually been arrested). In paying off the money that Marnie has stolen from Strutt (and then potentially paying the rest of the places where she has worked and then robbed from), along with the sense of the rich being able to buy themselves out of any sticky situation they get into, Mark introduces the idea of prostitution long before it gets raised in the final 'explanatory' flashback. Paying the money off in a way sullies Marnie still further as it illustrates the difference between an act performed for 'fun' or for compulsive reasons versus acts that may be morally wrong but which can be paid off, or which need to be performed in order to have enough money to live, for example Marnie's mother's prostitution. The scene following Marnie's robbery of Strutt shows her buying an ostentatious, and useless, fur scarf for her mother (a trophy from the hunt?) and paying for the upkeep of her favourite horse Faurio. So rather than needing the money because she is destitute, she is buying things in a childish manner, or to keep her inner child alive by maintaining her relationship with her mother and her 'toy' in her horse - expressions of a stunted childhood as illustrated by her (again, a little too on the nose) antagonistic relationship with the child her mother babysits, Jessie.

Mark either unknowingly (or knowingly but without a care for the cruel significance) morally dirties Marnie at the same time that he clears her name. He has a very cut off emotional side it seems, treating everything like a business transaction (again like Maxim de Winter). How much money will it cost to 'fix' things? He is driven, and has his authority to the viewer of the film undermined by, his own compulsions that he does not seem to want to acknowledge, if he is aware of them at all. Again this suggests his deep contempt for Marnie - that she needs to be solved and broken in a way that he himself does not.

And so to the honeymoon rape scene - and it is a rape, since Marnie is never a willing partner to it. Instead of being, say, 'raped into independence', it seems that this scene is about Mark raping Marnie into becoming a productive, and not destructive, member of society again, taking on the wifely duties of being available to her husband's needs whenever he wants them fulfilled. Even without the final explanation and 'mitigation' for the reason for Marnie's frigidity, and to give a horrible resonance to Mark's actions that it did not originally have, it is still an incredibly cruel and heartless way to make her face her demons. Again it raises ideas of prostitution - Mark has bought a wife, and she has to fulfil all of the obligations that come with that role.

In a way that brings me to why Mark would choose to become obessessed with Marnie, especially when it is such hard work to break her in and Lil is right there offering herself to Mark on a plate. It is about the hunt and capture, the thrill of the chase. Again there are links with The Birds here, and the available Annie Hayworth, while Melanie herself becomes the hunter and the rare bird at the same time - and then becomes perfect family material once she is passified at the end. The wild antics are just for show when what she really wants is stability - Marnie is the opposite in that Marnie herself wants the wildness, while Mark wants (or at least thinks he wants) her to become stabled. The superficially confident woman is broken down to be rebuilt in the way that her boyfriend wishes.

The hunt scene seems devastatingly pivotal in this transition, as Marnie first sees the things she previously enjoyed - the laws of the natural world and horse riding - become transfigured into a codified ritualistic, and highly mannered, act. The riders getting excited about the act of killing purely for pleasure prepare Marnie for bolting even before she becomes aware of the red of the rider's tunic. This drives her into spurring Faurio into a cross country gallop pursued by Lil (with Marnie symbolically becoming the prey now), until the accident when Faurio breaks his legs. I wonder if Marnie planned to cause the accident subconsciously so as to force her to destroy this significant element of her past life that she had placed such emotion onto? She pushes aside all requests for someone to shoot the animal for her (there never seems to be any shortage of volunteers!), needing to perform this action herself and kill off her past self.

Then the stage is set for the final confrontation, forced by Mark naturally, with her mother and explanation for her neuroses and sexual hang-ups. Once that is done, and mother abandoned, Mark has the perfect wife to mould to his wishes - or, after all her own attempts to escape earlier, will the tables now be turned and he will divorce her now that he has 'figured her out' and her mystery and interest for him have gone?

It is a really fascinating film, sometimes a little too obvious and mechanical in its allusions, but it definitely should be considered one of Hitchcock's major works.

- colinr0380

- Joined: Mon Nov 08, 2004 4:30 pm

- Location: Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, UK

Re: Alfred Hitchcock

Torn Curtain (1966)

"It's all right. I'm decent"